Norway's Longship sets sail

What other regions can learn from this scaling carbon dioxide storage and transport chain

You’re reading Terraform Now, a newsletter on the business of carbon removal. It’s been a while since the last article — thank you to my subscribers for sticking with me. My wife and I had our third child, and my work at Climeworks has kept me busy. But I’m back!

To support my work, please subscribe or share this article with interested folks:

TLDR

Norway’s Longship program takes liquid CO2 from a cement plant and a waste-to-energy plant and stores it under the North Sea floor

The program was delivered on time and (seemingly) on budget — a rarity in mega-projects

The Norwegian government understood exactly what types of risks the private market would not be willing to take, and when to give private partners the opportunity to use their unique skills

This balanced public-private approach should be studied closely by others around the world trying to create a carbon management industry in their region

At the end of June, a boat carrying many tonnes of CO2 arrived at Brevik, a Norwegian port on the North Sea. The liquid CO2 was off-loaded at the terminal, and will be sent via pipeline to a storage facility under the ocean floor. By the end of August, it will be stored away permanently, the final stage in one of the world’s most ambitious carbon-negative supply chains.

This was the first shipment of what has become known as the Norwegian Longship Carbon Capture and Sequestration project - I’ll call it Longship from now on. This is one of the most impressive carbon management projects in the world, for a few reasons:

Capacity: Longship has impressive ambitions, starting at 400,000 tonnes of CO2 per year and scaling up to potentially 50 million tons total this century

Public-private partnership: In addition to the Norwegian government, this represents a public-private partnership with at least 5 major companies

Speed: the program was announced in 2020, and five years later is fully operational

We live in a world where almost every mega-project takes twice as long and costs twice as much as it should. Longship is one of those rare, refreshing counterpoints that shows we can build important things quickly. That makes understanding this public-private partnership even more important for those looking for inspiration in other regions.

The basic idea behind Longship

Longship (or Langskip in Norwegian) is Norway’s flagship full-scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) initiative – the first of its kind to develop an entire CCS value chain in one coordinated project. If we think about the process of carbon removal in simple terms, Longship represents the final two parts of the value chain - transporting and storing CO₂:

Companies focused on capturing CO₂ have to charter a tanker to transport CO₂ to the Brevik terminal. In practice this means that all capture facilities need to be coastal or on major rivers, which is easy given the geography of Norway. The tankers drop off the CO₂ at the Longship terminal, where it is sent on a pipeline to the storage site, an old oil and gas well below the North Sea, where the CO₂ will find its forever home.

The public-private partnership behind Longship

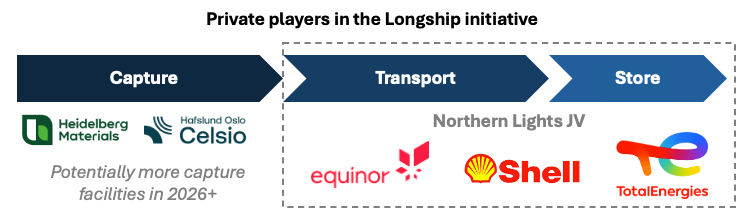

Announced in September 2020 by the Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg, Longship is a public-private partnership, meaning early risks were taken by the Norwegian government, while long-term implementation and management are up to private companies. It is private companies that are doing the actual carbon capture: Heidelberg Materials is currently capturing CO₂ at its cement plant in Brevik, and Hafslund Celsio is doing the same at Oslo’s Klemetsrud waste-to-energy plant.

Meanwhile, Equinor, Shell, and TotalEnergies formed the “Northern Lights” joint venture to handle CO₂ transport and storage – essentially building the offshore infrastructure to ship liquid CO₂ and inject it beneath the seabed. This includes the CO₂ tankers, the first of which is pictured at the beginning of the article.

Accelerating Infrastructure vs. Subsidies: Norway’s Approach

A central question about Longship is whether it’s essentially a state subsidy or an acceleration of new infrastructure. In practice, it is very much the latter – a deliberate government intervention to jump-start a CCS network that wouldn’t materialize on its own. The Norwegian state did indeed commit significant funding (on the order of NOK 16–20 billion, roughly $2–2.5 billion) to cover the upfront costs of the terminal, pipeline, and storage infrastructure.

The offshore transport and storage system in Northern Lights Phase 1 was 80% state-funded as part of Longship. However, rather than a perpetual subsidy to private emitters, this investment is about de-risking and building critical infrastructure that multiple industries and countries can utilize going forward.

Longship will not perpetually hand out taxpayer money — the Northern Lights JV will be responsible for the costs of maintaining transport and storage infrastructure going forward. This is in stark contrast to tax credits and OpEx subsidies that are common in other parts of the world.

Norway recognized that CCS has high barriers to entry: no single company would finance a CO₂ pipeline or offshore storage hub just to serve its own emissions. By providing large upfront grants and co-financing, the government essentially served as the lead investor in the CO₂ network. In other words, public funding was used to accelerate the development of an entire value chain, as opposed to expecting one player to build the whole value chain, and rewarding them after the fact.

Crucially, the state’s support was conditional and catalytic. The government insisted on cost-sharing and external contributions: for instance, funding for the Oslo waste-CO₂ capture was contingent on the project securing some of its own financing and EU support. This ensured the private sector had skin in the game and that Longship would spur broader deployment.

Geography and scaling potential

Norway’s foresight was broadly recognized. The EU classified Northern Lights as a Project of Common Interest, providing €131 million in Connecting Europe Facility funding – a sign that Norway’s investment attracted international buy-in.

Now that the infrastructure is becoming operational, it’s open-access: third parties can ship their CO₂ to Norway, paying a storage fee, which over time will further reduce the need for Norwegian subsidies. A map of the North Sea shows just how many carbon-conscious countries operate in the area:

And Longship has the scale to assure new capture entrants. Hafslund Celsio and Heidelberg are planning to produce ~440,000 tonnes of CDR per year, which should grow to ~750,000 tonnes each year once Hafslund scales up. Phase I of the Northern Lights project can handle up to 1.5 million tonnes per year. So about 50% of the transport and storage capacity is available for new entrants. It gets better — Phase II of Northern Lights was just approved for an additional 5 million tonnes per year.

And Equinor, a founding member of the Northern Lights JV, has a stated ambition is 30–50 million tonnes per year on the of Norwegian Continental Shelf storage by 2035 across a number of new locations — Smeaheia, Kinno, and Albondigas.

50 million tons a year of CO2 storage is hard to fathom. In the history of Carbon Removal to date, only ~30 million tons have been contracted — and that’s not what’s been contracted per year, that’s total contracts, spanning mostly the years 2028 through 2040. So on the surface this storage capacity looks way too ambitious.

But take a step back and look at where the market was in 2020, when Norway’s leadership announced Longship. At that point, only ~10,000 tonnes of carbon removal had been contracted! And yet the government went ahead, believing that if they built the infrastructure, customers will come.

And they were right! Just this week, we got hints that a Danish joint venture1 will leverage Longship for a waste-to-energy plant. This underscores the geographic advantage of Longship — it allows countries any country on the North Sea to access its facilities at a relatively low cost. In that sense it’s much more than a Norwegian project.

Closing thoughts on speed and scale (under budget)

The common path in carbon management right now is for governments to hand out three types of subsidies: up-front CapEx, ongoing tax credits, and ongoing OpEx support.

Norway did a few things differently. First, instead of spreading around tax dollars, they focused most of the subsidies on the riskiest CapEx part of the project — the transport and storage infrastructure. No single player would have been able to do this alone. This guaranteed that the project would get off the ground without committing taxpayers to never-ending subsidies and tax breaks.2

Second, Longship coordinated private companies and created partnerships capable of maintaining and expanding the infrastructure, hopefully with minimal government intervention and subsidization.

And third, it got out of the way of the private developers. At a time when many jurisdictions are imposing harsh restrictions on new projects (NIMBY), Norway streamlined permitting and licensing.

There’s one more component of Longship that I’d like to touch on. Research by groups within the Norwegian government agencies and academic institutions began in 2015. Real detailed planning started between 2017 and 2019. By the time the PM announced the project in 2020, there was broad consensus among most experts that this could be done, especially if Norway made a push to complete Longship quickly.

The key to mega-project management is detailed planning well before a commitment has been made. Norway’s foresight and patience to let the plans develop, followed by all-in CapEx subsidies to reduce risk, should be copied by every other region that wants to make large-scale carbon management projects a reality.

Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Vestforbrænding are partnering on what they call “Project Gaia.”

Recent experience in America suggests that relying on tax breaks over many decades may not be the best strategy, as the BBB bill has changed the eligibility criteria and volume of the 45Q tax credits