Is storing carbon dioxide in concrete a winning business model?

How investors and environmentalists should think about this emerging technology

You’re reading Terraform Now, my newsletter on the business of carbon removal. To support my work, you can subscribe here or share this article with interested folks

TLDR:

There are a lot of businesses focused on putting CO2 in concrete to replace geologic storage

The amount of CO2 we’ll practically be able to store in concrete is smaller than most estimates

CO2-infused concrete is more expensive than geologic storage. The most cost-effective de-carbonization option for concrete companies will be paying for offsets to put CO2 underground

CO2-infused concrete will be hard to sustain as a business model without muscular government support, similar to what California provides today

I am writing this from San Francisco International Airport, which is made in large part from concrete infused with carbon dioxide (CO2). A company called Blue Planet captures CO2 from a local natural gas plant, creates a carbonate by combining it with calcium, and uses that as part of aggregate, a gravel and sand mixture that makes up ~80% of concrete.

Blue Planet is not alone. In recent years, many companies have developed technology to infuse CO2 in concrete:

Business models vary, but there are three broad approaches:

Integrated removers like Blue Planet own the source of CO2 with carbon capture equipment on power plants or Direct Air Capture plants (DAC). They then mix the CO2 into concrete, sometimes at the construction site

Materials developers create a process to get CO2 into concrete in a pilot setting and license the technology to concrete suppliers

Concrete manufacturers buy CO2 and mix it into concrete using a licensed technology

And there are two different ingredients in concrete that can act as storage for CO2:

Cement (~15% of concrete by mass) is the active ingredient in concrete, the yeast to the bread. Since it has to be fired in a hot kiln, it’s the source of most of the emissions associated with concrete

Aggregate (~85%) is the gravel, sand, and other bulk materials that are mixed in with cement before pouring the concrete

A decade ago, most companies focused on putting CO2 in cement because it is the source of emissions1. Recently, companies have shifted to infusing aggregate for two reasons. First, there’s so much more aggregate — on average concrete has 6x as much aggregate vs. cement. Second, aggregate is less delicate than cement, meaning it can accept a variety of materials without putting the overall concrete mixture at risk. This makes aggregate a better path for maximizing the amount of CO2 that can fit into a given ton of concrete.

All of this is very exciting — these companies are doing cool work, and are approaching the problem in a more reasonable way than they were a few years ago. And there are other good reasons companies and investors get excited about CO2-infused concrete:

Humans pour a lot of concrete

Concrete manufacturing makes up 8% of global emissions, so it seems like a good industry to de-carbonize

Sticking CO2 underground seems wasteful when you could actually use it in something, like building an airport

Putting CO2 in concrete is permanent, unlike using CO2 in recycled fuels or agricultural products that might re-release it into the atmosphere2

But in the long run, concrete will not play a sizeable role in carbon removal for three reasons. First, most concrete will be poured in countries that can’t afford (and won’t prioritize) carbon neutral concrete. Second, concrete as a storage option for CO2 will be too small to matter once CDR scales. Finally, it’s just too expensive and will require muscular government support to succeed in the long-run.

Countries that are doing the most on carbon removal pour the least concrete

Bill Gates likes to say that humanity is going to pour enough concrete to build a new Manhattan each month for the next 40 years. He glosses over where all that concrete is going to be poured3:

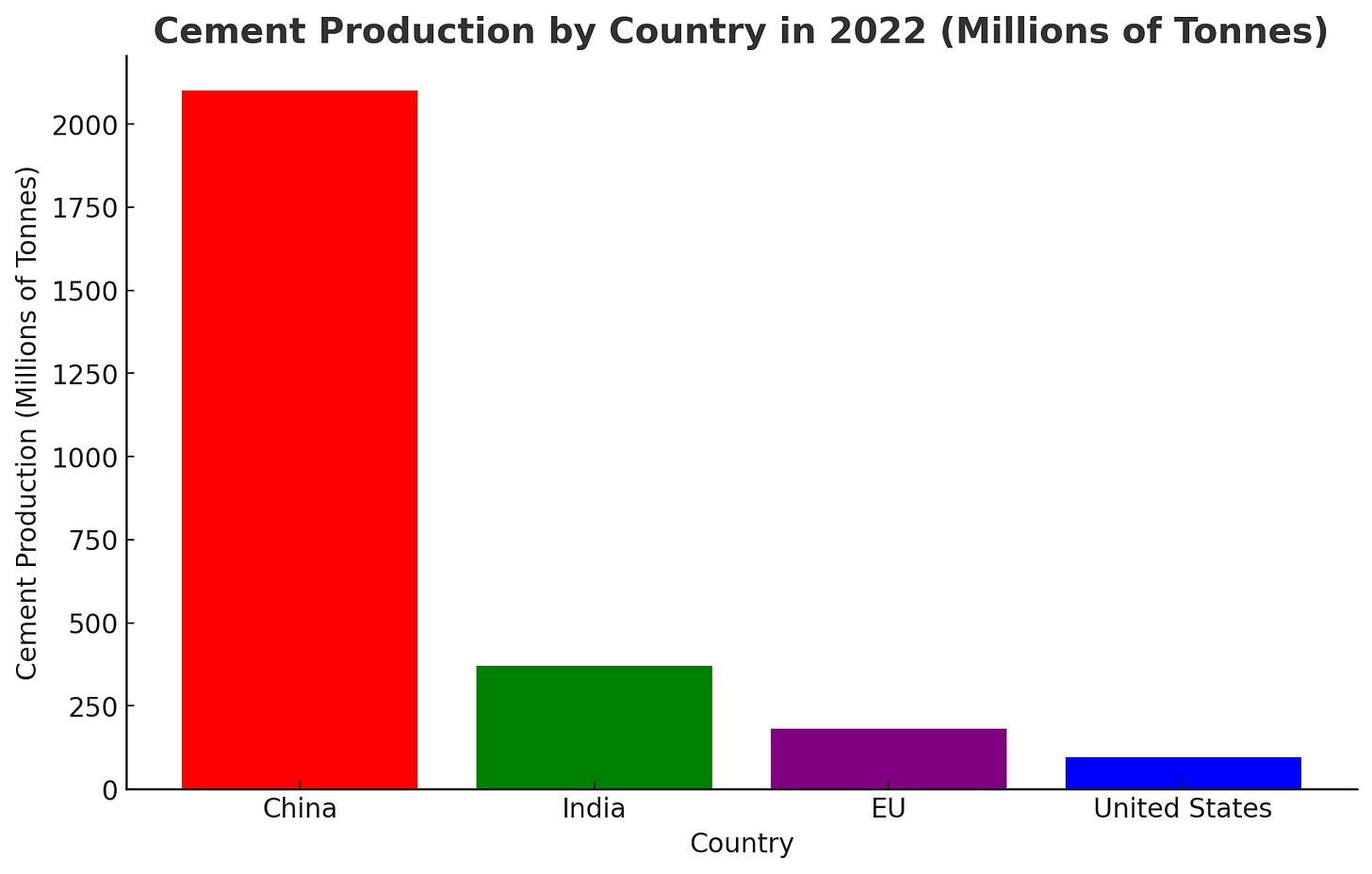

About half of all concrete in 2022 was poured in China. The United States, with a quarter of global economic output, poured only ~3% of the world’s concrete, and the EU poured just ~5%.

In the 21st century, ~70% of the world’s concrete will be poured in countries with a GDP per capita lower than $20,000 per year. We have good reason to believe that countries with fewer economic resources are unlikely to prioritize carbon removal. Policy in these countries will be, and should be, focused on creating a thriving middle class.

Take China, which has no clear plans to remove carbon on a large scale. Pilots of carbon-negative concrete have stalled, and I have trouble finding Chinese companies focused on scaling this tech in the last 3 years. And this makes sense! China’s Communist Party is focused on solving a slow-moving housing crisis, building a world-class military, and creating a healthcare system that can serve their aging population. In the eyes of Chinese leaders, who are all over 60 and unlikely to live to see the impacts of climate change, these are way more important initiatives than de-carbonizing concrete.

Concrete is a sizeable storage basin, but is tiny compared to geologic storage

Every year ~30 billion tons of concrete4 are poured on Earth. Perhaps ~8% of any given ton of concrete could be mineral-state CO25, which means about 2.5 billion tons of CO2 storage potential each year.

Seems like a lot, but relative to geologic storage this is simply tiny. This stretch of land, along the coast of Texas and Louisiana, has ~125 billion tons of potential geologic storage — that’s decades of global concrete CO2 storage. The world as a whole has between 2 and 16 trillion tons of storage potential. There’s at least 1000x more geologic storage than concrete storage.

It’s worth noting that relative to the current scale of Direct Air Capture and capturing CO2 at emission’s source, concrete is indeed large. And relative to non-storage markets for CO2, like fertilizer, soda, etc., concrete is also very large.

Even if we assume that only countries with high GDP per capita could scale CO2-infused concrete, concrete dwarfs these sources and uses of CO2:

This is why folks are excited about concrete — it seems like a better solution than, say, fertilizer. But if you take a step back and consider the bigger picture, it’s just too small of a storage basin to matter.

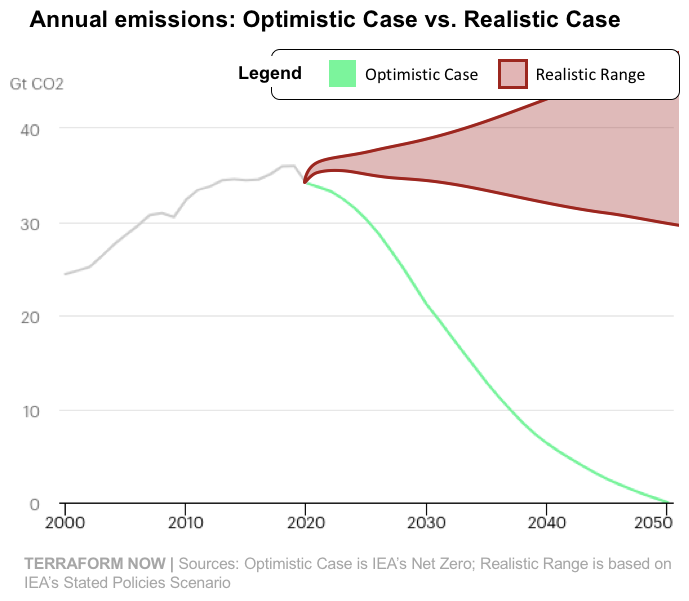

Each year, we emit ~40B tons of CO2e6 into the atmosphere. Optimistic assessments have this going down to 0 by 2025, but it’s more likely that we stay at about 40B tons, give or take ~25%, for the foreseeable future.

To reach the elusive goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions, carbon removal needs to take out tens of billions of tons of CO2 each year.

Geologic storage can easily handle all of this capacity. Concrete can handle between 0.1% and ~30% of this capacity, depending on your assumptions.

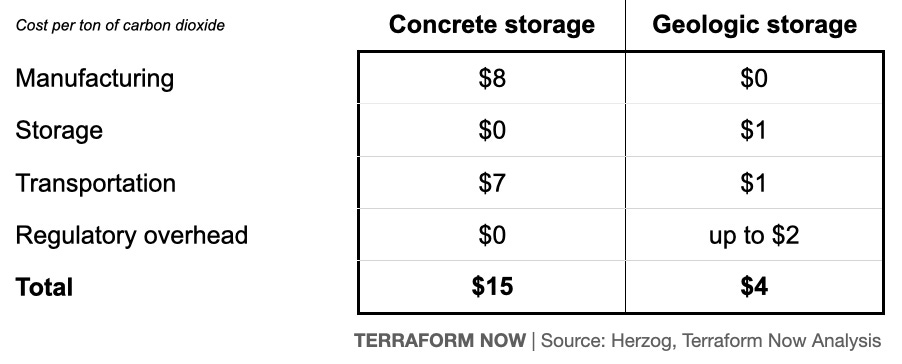

That said, if putting CO2 in concrete were cheaper on a per ton basis, then we should preferentially fill up the concrete storage basin first, then move onto geologic storage. But this is not the case — geologic storage is much cheaper.

Concrete storage is more expensive than geologic storage

Let’s lay out a few assumptions:

All-in costs of pouring one metric ton of concrete = $100

Number of tons of concrete that can store one ton of CO2 = 8

Cost to transport a ton of CO2 by truck = $7

Cost to capture a ton of CO2 from a power plant (the cheapest way) = $50

Additional manufacturing cost to add CO2 into aggregate mixture = $1 per ton of concrete

Putting all that together, 8 tons of regular concrete cost ~$800 to pour, while 8 tons of concrete infused with CO2 is ~$865 — making CO2-infused concrete ~8% more expensive than regular concrete.

What’s more important is comparing the cost to infuse CO2 in concrete vs. storing CO2 underground:

It’s ~3x more expensive to put carbon dioxide in concrete vs. in the ground! Much of the delta comes from lower transportation cost for geologic storage. For construction projects, which are distributed all over the place, CO2 will have to be brought out by truck. For geologic storage, we’ll build pipelines from the capture facility to the storage site, and these are very cheap on a per ton basis:

Now imagine a carbon-negative concrete manufacturer starting a project on an expansion of a local highway. They budgeted $2M to put CO2 into their concrete. Their sustainability team presents two options: (1) put the CO2 in concrete or (2) put the CO2 underground, in geologic storage. Again, let’s assume this company is buying CO2 captured from a nearby natural gas plant at the going rate of ~$50 per ton.

The concrete company could spend the same amount of money and remove 6,700 tons, or 21%, more than if they put CO2 in their own concrete mixture. They could also save an extra manufacturing step, and delete the logistics complexity of bringing extra deliveries to busy construction sites.

So the most cost-effective solution for concrete companies looking to de-carbonize is to pay for offsets to put CO2 underground.

So how are concrete companies surviving?

Because it is a more expensive solution, CO2-infused concrete makers would not have a competitive product in a free market. But California, where CO2-infused concrete has been most successful — and where Blue Planet is based — has heavy- handed government intervention. Blue Planet benefits from a long list of policies:

Environmentalism is a guiding light in California’s many building codes

California has a carbon price, currently at $56 - $72 per ton (compare to ~$7 per ton in China)

The US federal government has tax credits worth ~$60 per ton for carbon removal used in concrete7

California voters shrug off cost overruns on big projects, so adding concrete that is 8% more expensive to an airport doesn’t put politicians in hot water

Californians take pride in being early adopters of technology

For CO2-infused concrete to take off, you have to believe that countries like China, India, and Indonesia — the big pourers of concrete in the 21st century — will have political economies that look like California’s. That’s not a bet I’m willing to take.

Generally speaking, countries prioritize the climate solutions that are most of interest to their success in other ways. Let’s return to China. Prices for solar photovoltaics and batteries are dropping rapidly, in large part because Chinese factories are pumping them out at unprecedented rates. This is a direct result of Communist Party policy to subsidize manufacture of export goods. The Party is motivated to increase manufacturing to keep the Chinese economy growing as it enters a new phase where it is less reliant on housing and infrastructure to drive growth. Things like carbon-negative concrete do not help policymakers in China with these (or other) goals.

And emerging economies are much more likely to imitate China than California. That dampens the outlook for CO2-infused concrete companies.

This is the third Terraform Now’s series on CO2 storage. Part 1 is all about why CO2 storage will be so important and what types of rock formations are best suited to storage. Part 2 covers the main obstacles to storage and why it takes so long to build an underground storage facility.

Cement has to be fired in a kiln before it is ready to pour — this baking accounts for most of the emissions that comes from manufacturing and pouring concrete

Carbon dioxide, when it enters the concrete aggregate, binds with calcium to create calcium carbonate, a mineral. Even if the concrete structure is demolished, no carbon dioxide is released. If this sounds familiar, that’s because Heirloom’s DAC technology uses a similar process, where limestone captures carbon dioxide and bonds it to calcium. This chemical process is typically called ‘mineralization’ in CDR lingo

Eagle-eyed readers will note that this chart shows cement production rather than concrete poured. Cement is tracked by analysts more rigorously because it is manufactured, whereas concrete is mixed and poured at the construction site. So when looking across borders, cement is the best place to start. Since most constructions the world over sites use ~15% cement and ~85% aggregate, we can extrapolate amount of concrete poured even if mixtures vary by application, region, etc.

Estimates for global concrete poured each year aren’t very accurate, since analysts don’t measure concrete at the construction site. A more reliable metric is the amount of cement produced annually, which is around 4B. As we’ve seen, concrete is 15-20% cement and 80%-85% aggregate, and I use these numbers to get to ~30B tons of concrete

A generous assumption — it’s likely to be much lower

CO2e is shorthand for carbon dioxide equivalent, meaning the amount of greenhouse gases we release into the atmosphere with equivalent warming effect carbon dioxide (e.g. methane, nitrous oxide, etc.)

Concrete manufacturers won’t benefit from this unless they are integrated shops like Blue Planet